Not that UAP aren't a multifaceted, multidisciplinary subject: a challenge to physics, a psychological phenomenon, a socio-cultural topos, a great subject for a movie. But at the end of the day, it's about solving a mystery, investigating these phenomena, hypothesizing and finding evidence. Doing the work of scientists.

Publications dealing with UAP and academia date back at least to the 1970s, when scientists from different professional societies addressed the issue of whether scientists were also experiencing UFOs (the then-preferred acronym) [1, 2] The underlying second question was, of course, whether these scientists take the subject seriously.

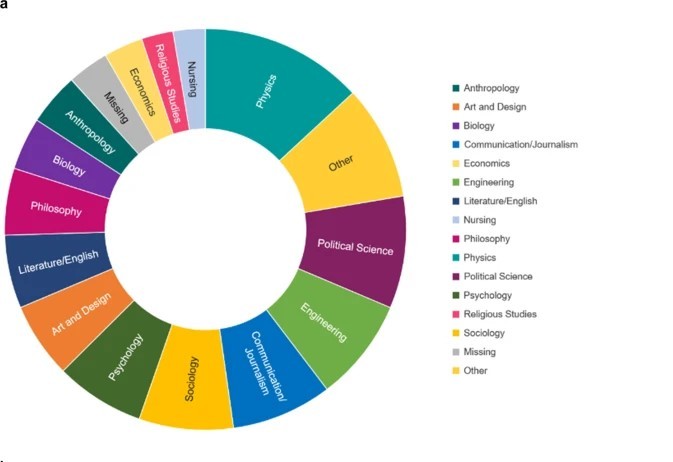

Fifty years later, exactly this question is still under scrutiny: With the 2023 paper “Faculty Perceptions of Unidentified Aerial Phenomena”, Dr. Marissa Yingling and her co-authors showed that today, “faculty think the academic evaluation of UAP information and more academic research on this topic are important“ [3]. In a national survey, faculty members of 14 different disciplines from 144 universities in the USA had been asked about their opinion on UAP. The background was of course the new political debates on this matter, while scientific research on UAP had been a taboo since the 1970s, following the infamous Condon Report, which at least in its "Conclusions and Recommendations" suggested that there was nothing to be learned from this topic [4].

So, are UAP something to be ridiculed and not studied in academia? This August, the associate professor of social work at the University of Louisville followed up with the second part of her national survey, in a longer article published in the journal Humanities and Social Sciences Communication. [5]

Conducted between February and April 2022, the participating university personnel were also asked the following questions:

- If you conducted UAP-related research, how concerned would you be that your work would jeopardize tenure or promotion?

- If you conducted UAP-related research, how concerned would you be that your academic colleagues would give you a “hard time” or ridicule you?

- How much would knowing that a colleague or otherwise credible member of your field was conducting UAP-related research devalue or diminish your perception of their other conventional scholarship?

- If a colleague in your unit under consideration for tenure or promotion conducted UAP-related research, would this negatively influence your evaluation of their case?

- “If UAP could be explained by an unknown intelligence, how important would this be to academic consensus theories and knowledge?”

- “If UAP could be explained by an unknown intelligence, how important would this be to your discipline?”

The results of the study paint a mixed picture: There were “faculty in the study who said this subject deserves no attention whatsoever. Some espoused apathy. Some even thought that researchers in this area should be ‘ashamed’ or are ‘bought off or just dumb’. Others viewed extant stigma as contrary to the pursuit of knowledge, prohibitive to scholarly interests, and fostering abandonment of responsibility to critique narratives”. Interestingly, the participants who reported the least concern about ridicule for researching UAP were from disciplines that did not consider themselves relevant to assessing this issue: Art and design departments were the least concerned, while physics – a discipline important for dealing with the physical aspects of UAP – and engineering were the most concerned about being ridiculed and voted against by colleagues who work on UAP. Similarly, “newly minted PhDs appear to be the most open-minded toward UAP, if only marginally”. These findings underscore an ongoing tension between academic freedom and the social acceptability of certain research topics. As Dr. Yingling writes, “cultural baggage impacts this topic“.

The new study based on the widespread survey from 2022 highlights the need for academia to engage more openly with stigmatized topics like UAP, balancing curiosity and scientific rigor with the potential risks to professional standing. It suggests that academia has a critical role in evaluating and understanding such phenomena, despite the prevailing stigma. And yet, apart from studies dismissing any anomalies or the need for new hypotheses in light of existing UAP, located more in the psychosocial fields, there is no large-scale institutionalized scientific work on UAP today (and no funding for it, as the study examines, too). But there are new developments. The German “Interdisciplinary Research Center for Extraterrestrial Studies” (IFEX) at the Julius-Maximilians-University of Würzburg is one of them, with the first professorship actively dealing with the physical aspects of UAP and how to measure them [6]. And while Prof. Hakan Kayal, a space technology researcher, may still be an individual in this field, his center’s associate members include well-known organizations and researchers from the UAP field.

And this might be the key to applying rigorous scrutiny to the study of UAP, as the study concludes: If academic institutions are to engage seriously with the subject of UAP, they must also engage with the pile of existing work from over 77 years, including picking out the valuable pieces from this pile of mixed engagement with the subject through all the voluntary activities of hundreds of individuals and communities, from religiously motivated reflections to premature dismissals. And it is the volunteers who are striving for a scholarly debate on the subject that are indebted to present their work on UAP as relevant. Simply making demands will not improve a strained relationship; scientific work is first and foremost cooperative work.

References

[6] Interdisciplinary Research Center for Extraterrestrial Studies (IFEX)